We are coming out of the post-surgery haze. Having come out of hospital one week after the operation, Ben started at a new school exactly two weeks after surgery. We had feared that he wouldn’t be well enough and might miss the beginning of term, so it felt like a huge win to get him there in one (slightly bruised, stitched together) piece.

James has taken a significant chunk of time off work so we have had the luxury of introducing Ben to school slowly, calmly, with both of us around to make it work. We have been able to take him in together, learning how to drive into central London without killing a cyclist or getting embedded in a stationary traffic jam, and pick him up early. Max has come in with us and got to know the new school. We have all been able to meet the staff and see where Ben spends his day. It’s all been significantly less stressful than I anticipated.

It’s not all been plain sailing. Until earlier this week Ben had periods of profound unhappiness which couldn’t be resolved with paracetamol, or ibuprofen, or TV, or books, or lying in bed. There are few things more sapping than spending four hours with a child who is really unhappy and being apparently incapable of making things better. Maybe he had a headache (there is, after all, stuff in there that wasn’t there before), or a tummy ache (ditto), or the wounds are uncomfortable, or he’s just really bored of being with us at home. Not fun. But if someone told me pre-surgery that Ben would start at school two weeks later and be largely cheerful (or at least not miserable), I would have taken it.

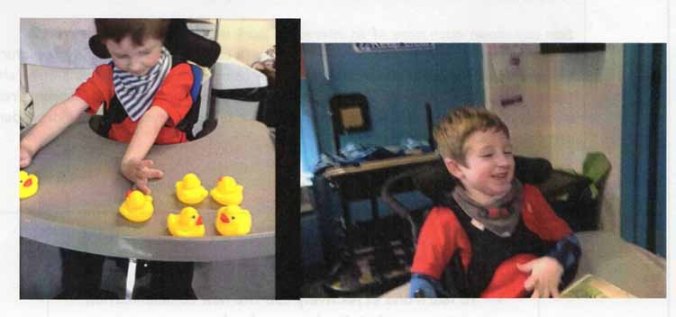

He’s now done two weeks and he isn’t just putting up with school, he is really happy. As we walked in on the first day, Ben was all smiles. He has loved school thus far and he knew he would enjoy it, and he was right. That is partly because he likes learning and the variety of a school day, and partly because it’s an excellent school. James and I were far more nervous than Ben, but the staff are so obviously capable, receptive and skilled that we have had no choice but to happily leave Ben there and go for lunch in Clerkenwell or take Max to the Museum of London, again.

I’ve described before the importance, and marvelousness, of one’s disabled child going to a really good school. We have been fortunate enough to find two. Ben has moved schools because we, and the professionals working with him, felt he would benefit from more specific and specialist input so he has moved from a school for children with a range of special educational needs to a school for physically disabled children. He, and we, loved his previous school and were sad to leave. We all made very good friends there and Ben was lucky to be taught and supported by lovely, skilled people for two years. Saying goodbye to them all involved a lot of weeping, for once not just by me.

As part of leaving, Ben got his last school report. We spend a lot of time reading expert reports about Ben that are, necessarily, factual and focus on problems. Ben’s report was the exact opposite of this – hundreds of words of enthusiasm and celebration. It was a joy to read and was written evidence of the can-do attitude of his lovely teacher. Forgive me as I quote some of my favourite bits – comments that could only be made by people who have taken time to really get to know Ben and see past the immediate obstacles to communication and learning:

‘Children and adults are drawn to Ben’s fun friendly nature and positive attitude.’

‘One of Ben’s many lovely qualities is his empathy. If another pupil receives praise or is celebrated for an achievement Ben will start to beam and become very excited.’

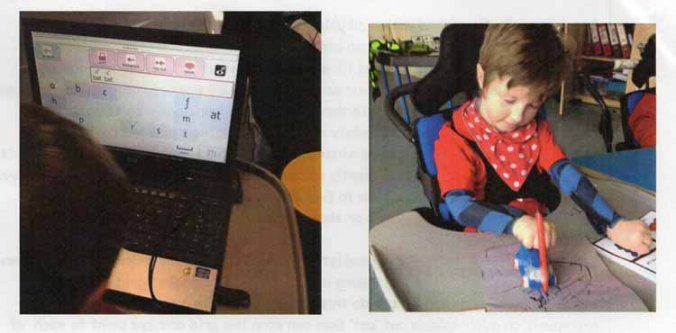

‘Ben can communicate with adults using his communication board, his PODD book, symbols or just by gesture.’

‘Ben has really flourished with phonics activities this year, and with the continued support he receives from his family he has excelled in this area.’

We are incredibly proud of him, so pleased he’s had such a brilliant experience of school so far and so thankful for such talented teachers and assistants. What a geek! Like mother (and father), like son.